“The river looked at him with a thousand eyes- green, white, crystal, sky blue…. It seemed to him that whoever understood this river and its secrets, would understand much more, many more, all secrets.”

– from Siddhartha, Hermann Hesse

In the cold and rain, with thousand-year-old redwoods standing watch, the Smith River showed itself to me for a moment.

It was not gentle. Alone with trees as solid as mountains and the presence of Taoist sages, serpentine liquid running its wild song across the rocks, both forces way larger than me, kindled a primal fear. You know those moments when you see the world in a different way than you ever have? How it can be disorienting. Shake your bones.

Staring at the river for so long, the rocks that line it begin to morph and change. What is this emerald flowing creature? Meandering through the land. Cutting its way through mountains. Sometimes only a trickle. Sometimes a roar.

How does it find its way together? From a raindrop on top of a mountain to a trickle down the side, to a stream, to this hundred-foot-wide river? And how is it that we got so lucky? We could have had turpentine running in streams over the earth. Or liquid nitrogen. Or chocolate milk. (whoops, daydreaming again)

But we have water, our life-giving elixir, coursing in veins across our world. Always changing and always the same.

the journey

Driving from San Francisco up through Petaluma, Ukiah, Willits, Eureka, and Crescent City to the bed of the Smith River, it was apparent that we were in river country. First the Russian River. From a land of grass hills and oak trees to deep green redwood forests. Then the Eel River criss-crossing back and forth under the 101. Then the Mad River. Then the mighty Klamath. From who’s waters we ate wild Chinook Salmon smoked for five days by Yurok Indians. And finally, the clear and green Smith River.

This is the land where California’s rain falls. The green and wet, sparsely populated North.

tracking the river

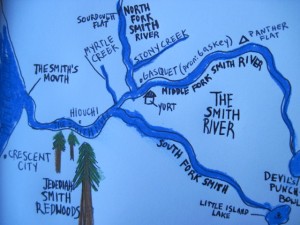

I had this notion that I was going to track the Smith River. So that I could understand it better. It turns out rivers can be challenging to track because of where they come from. Lone drops of water finding themselves sinking into the land to meet up with other drops, seeps, trickles, creeks, rivers. Most simply, the headwaters or the source of a river is the place from which water in the river originates- maybe a spring, marshland, or creek. A tributary is a stream or river that flows into the main river.

be challenging to track because of where they come from. Lone drops of water finding themselves sinking into the land to meet up with other drops, seeps, trickles, creeks, rivers. Most simply, the headwaters or the source of a river is the place from which water in the river originates- maybe a spring, marshland, or creek. A tributary is a stream or river that flows into the main river.

In the Smith’s case, three decent size rivers, the North, Middle and South Forks of the Smith have their own headwaters and meet up to create the main Smith River. From around the town Gasquet, the Smith River winds its way through redwoods and into wetlands until it makes it to its final destination, the mother of all bodies of water, the Ocean, about five miles South of the Oregon border.

the river’s work

Watching the Smith, you get an idea of how much work a river does. Moving water, nutrients and material from one place to another, providing a myriad of different homes for the plants and animals that live next to and in it- salmon, red alder, steelhead trout, big leaf maple, frogs. They are also a source of food for all us animals and of course, contain the liquid that sustains every form of life we share the planet with. Rivers sculpt and form our landscape.

Watching the Smith, you get an idea of how much work a river does. Moving water, nutrients and material from one place to another, providing a myriad of different homes for the plants and animals that live next to and in it- salmon, red alder, steelhead trout, big leaf maple, frogs. They are also a source of food for all us animals and of course, contain the liquid that sustains every form of life we share the planet with. Rivers sculpt and form our landscape.

the last of its kind

The Smith River has the distinction of being the last undammed river system in California. That means that every other major river has dams on it.

Dams hold our water, and save it up for when there is no rain in the summer or in dry years. But I wanted to understand what a river that has no dams on it acts like. Turns out the Smith is a wild creature.

Talking to a ranger who’d lived around the river all of his life, we found out that the Smith’s water level goes up and down dramatically between the summer and winter, and also from day to day. Flooding is a natural part of a river’s cycle, one that humans who like building their houses on floodplains like to control, but a part of the river’s lifecycle that is essential. We saw giant redwoods whose bases had been covered by silt and nutrient rich material from the Smith’s past flooding. Flooding brings nutrients and materials to the thriving eco-systems alongside it.

I was also pleased to hear that the Smith River had an absolutely amazing run of Chinook salmon this year. Coming  from the Bay Area, where news of the local salmon runs is increasingly depressing, I was happy to hear it. To get an idea of numbers, the Rowdy Creek Hatchery on the Smith counted a total of 687 Chinook in the last three years. This year, in one year, the hatchery counted 2,775 Chinook just in Rowdy Creek! The ranger we spoke with said he was at a fishing hole, during the run, as 20 large Chinook fought their way up the current. He said, at up to 75 pounds, they looked “like little whales cresting.”

from the Bay Area, where news of the local salmon runs is increasingly depressing, I was happy to hear it. To get an idea of numbers, the Rowdy Creek Hatchery on the Smith counted a total of 687 Chinook in the last three years. This year, in one year, the hatchery counted 2,775 Chinook just in Rowdy Creek! The ranger we spoke with said he was at a fishing hole, during the run, as 20 large Chinook fought their way up the current. He said, at up to 75 pounds, they looked “like little whales cresting.”

In rivers with dams, the chances of a large run being able to happen are a lot less as migrating salmon needs miles of streams and healthy stream beds on the river they were born in, in order to reproduce. In the Central Valley and Sierra Nevadas, only ten percent of suitable spawning habitat remains. (Intro to Water in CA)

Makes you think. Is there a way we can store water and allow the river to do its many jobs at the same time?

our water is a river

I reminded myself a million times watching the Smith that this river, or rivers like it, are (unless you drink groundwater) what comes out of my tap. So many times when I drink water, I forget that I am in direct connection with a living thing- a river- which changes its mind, has a job, provides homes, and nourishment and beauty for our eyes and ears, and is constantly changing and shaping the way the world looks to us. The Tuolumne, the Colorado, the Russian, the Feather River. No matter where you live, you have a connection with a wild river that has its story to tell.

me and the Smith

I sat by the river most everyday and listened. The Smith had much to tell. Like every river I have sat by, the Smith told me a story of change. Looking at its whirls and eddies and flows I couldn’t not notice that every second was something new, that the only constant in a river, and in the world for that matter, is change.

Before I got to the Smith, I felt like I’d been holding on a bit too tight- to the way I think of myself and the world. I kept having visions of submerging myself in the water, letting the river wash all the extra away.

And so I did. Lowered myself into the startlingly cold Smith and let go. Of all the brown stick debris, wondering leaves, the silt of the city. Bringing me into the main channel of movement, surrender, flow.

Thank you to James for being a sweet traveling companion! (and for the great pictures). Stay tuned as I journey next week to the dry South of California, to the Salton Sea and the great (very thirsty desert) at our southern end.

great post as usual!