“If it keeps on raining, the levee’s going to break.”

– Led Zeppelin

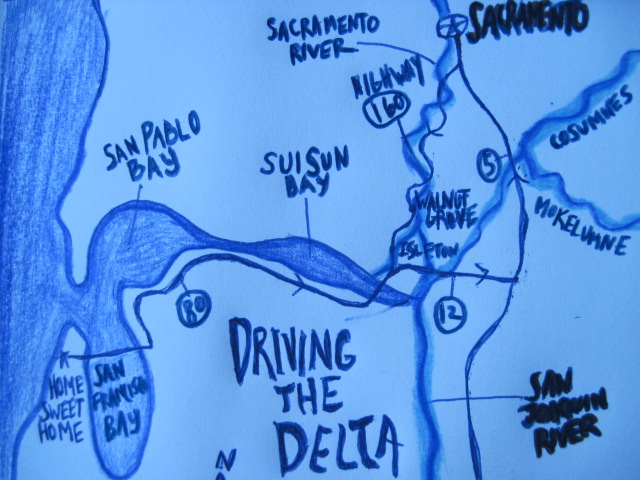

Took a drive through the Delta the other day. It was a beautiful drive, complete with picturesque houseboats floating down the Sacramento, sultry heat, and strawberry popsicles. I let myself soak up the delicious end-of-summer day. But, a part of me was confused.

The fly in my ointment: a part of me that couldn’t reconcile what I imagined the Delta would look like and what it looks like in reality. I had been looking at pictures and reading definitions and trying to understand what I might see. You were there with me, dear reader, as I was piecing it together in my intro to the Delta last week.

The thing is, I know the Delta is in trouble. All those things we talked about last week- lack of water going through the Delta, its fragile ecosystem. But I still had in my mind, a mixture of bigger and smaller marshy waterways that were disturbed and had less water in them than they should, but that still looked like a Delta. And that’s not what I saw.

week- lack of water going through the Delta, its fragile ecosystem. But I still had in my mind, a mixture of bigger and smaller marshy waterways that were disturbed and had less water in them than they should, but that still looked like a Delta. And that’s not what I saw.

It’s not all bad. Not at all. It was impressive to see how humans can shape and utilize the environment to our benefit. Humans have turned the Delta into a carefully constructed agricultural and recreational paradise, as well as the central piping that gets water down South. The Delta’s fertility (due to river sediment) makes it the perfect place for farming. Except for all that water. But if you can control the water, then you not only have the perfect soil, but a water source with which to grow things. And, the large channels happen to be perfect for boating and watersports.

In this man-altered Delta, the Sacramento River moves along in a manmade-looking channels. Big waterways connect with little waterways- aqueducts and ditches- all manmade. On the side of the waterways, farmland stretches for miles. Farmland that is sunken, most of the time, lower than the waterway next to it. Fields surrounded by raised earthen walls- levees. The levees keep the water out and help organize the gigantic effort to get water to where its needed.

All day long, we drove on levees- where all the roads run. With sunken farmland to one side and canals of water on the other. Passing signs for Brannan Island- an island without water around it. And most surprisingly, not passing wetlands, except for a few small patches. While I’m sure it was partially the route we took, I am still surprised at what I saw. What people call the Delta doesn’t resemble a delta in any way.

It’s a pretty place on the surface. There are a ton of fun things to do. Boating and

water sports, fishing and relaxing, sunbathing and drinking beer. But if you look at the Delta a little deeper, the precariousness of its current nature becomes apparent.

The effort it takes to maintain an area that should be underwater is one piece of this. Not only is it farmers who have to maintain their levees, most of the population of Sacramento would be underwater if it weren’t for the constant struggle to keep water out. Reading newspaper headlines, you’ll get a sense that the other levee that threatens to break is the fight over how water that moves through the Delta should be used.

Pumping plants northwest of Tracy, California suck water from the Delta and into a series of canals that deliver the water to urban areas in Southern California as well as to farms in the Central Valley. There is only so much water and we have allocated Delta water to its limit.

You can imagine that with all this human activity organizing, controlling, and siphoning off water from the Delta, that it is not in good shape ecologically. The animals that call the Delta their home have had to rearrange their lives around our uses, many brought to the brink of extinction- salmon and Delta smelt among them. And the functions the Delta had, as a major wetland, have almost come to a complete stop.

Driving the delta, I saw what a productive place we’ve created, and at the same time, felt the darker, imminent threat of the many levees that hold the Delta up, physically, socially, and ecologically close to breach.