So yes, my friends, we have learned a lot about the Delta in these last two weeks. What a delta is supposed to be: the marshy capillaries that connect freshwater rivers to oceans and bay. And what our Delta is: a fragile, strangely beautiful place that has undergone a radical, human transformation and whose future rests in the hands of every Californian.

Most people recognize that if we are going to move in a healthy direction for the Delta, many different groups of people will have to work together: farmers, environmentalists, urban folk, fisherman, residents, and recreational enthusiasts. Without working together and without support, the Delta will surely collapse; ecologically, culturally, physically, etc.

One of the more controversial plans you are certain to hear a lot about in the future is the possibility of a peripheral canal. What is it? It is an engineered canal that would extract water from rivers north of the Delta, bypassing the Delta altogether, so that water can travel unimpeded to the South.

There are many, many opinions about the canal. I, myself, am not convinced that building a several billion dollar canal is the way to go. Some, such as the Public Policy Institute of California, say that a peripheral canal will take pressure off the Delta environmentally and that long term, it is a more cost effective method because global warming and earthquakes are likely to make maintaining levees costly and nearly impossible.

building a several billion dollar canal is the way to go. Some, such as the Public Policy Institute of California, say that a peripheral canal will take pressure off the Delta environmentally and that long term, it is a more cost effective method because global warming and earthquakes are likely to make maintaining levees costly and nearly impossible.

Others say that a peripheral canal may make the Delta’s situation only worse- possibly extracting more water from its already low levels, ruining farmers’ livelihoods and making water quality in the Delta worse.

While it’s a bit hard to decipher who’s who in this highly political battle, I would not support the canal unless there were guarantees that protecting the Delta’s ecosystem is a mandatory part of its plan and also studies that show it is truly the best option for our watery health. I am inherently distrustful of plans that make California’s waterways even more manmade and controlled and also, have the potential to make a few people wealthier. When it becomes a hot topic again, please, dear reader, rely on your critical reasoning to decide what to support.

Besides engineering, the future of the Delta will be determined by our awareness and support of it. Crucial to our watery health and circulation, the Delta is important beyond all of our needs and demands on it. Locally and statewide, agreements can be made to honor the functions of the Delta and its inhabitants as well as support our human needs. Those of us in the Bay Area have the opportunity to work on the ground, helping to restore the Delta piece by small piece. (see below for restoration opportunities)

And in every corner of California, we need to recognize that our relationship to water will determine the fate of the Delta. The less we use, the more we recycle in innovative and energy-efficient ways, the more we contribute to the survival of our Delta, our watery heart.

For more information about the Delta or to get involved, go visit and see for yourself or look at:

Cosumnes River Preserve– large scale restoration of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. A great place to learn about the original, natural functions of rivers on the valley floor as well as how humans can coexist with the natural functions of the Delta.

Discover the Delta Foundation- “an unbiased perspective” on the Delta

Restore the Delta– local Delta organization dedicated to the agricultural, ecological, and recreational health of the Delta.

Stay tuned next week for a visit to Cosumnes River Preserve, an incredible example what the Delta used to look like and also, what it could look like in the future.

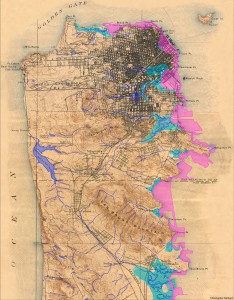

would see two of our major rivers, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin, as solid blue lines, but in reality, the map should show dotted lines; to show all the stretches that have been dewatered, being diverted to other uses such as drinking water in Southern California and farming in the Central Valley.

would see two of our major rivers, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin, as solid blue lines, but in reality, the map should show dotted lines; to show all the stretches that have been dewatered, being diverted to other uses such as drinking water in Southern California and farming in the Central Valley.