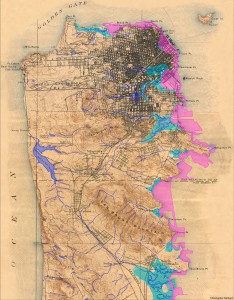

As I mention in the Author section, this project was partly inspired by a meeting with Islais Creek, a forgotten river of San Francisco. Beside the creek, I saw a map that showed the major historical and strangely absent rivers of San Francisco. Seeing that map was a powerful experience. Almost like I’d been given a gift and had it taken away in the same moment. But as I continued to wonder where these bodies of water went, I realized that the gift of those rivers had not been taken away completely. They were just under my feet. Somewhere buried. And that changed my whole experience of walking around San Francisco.

As I mention in the Author section, this project was partly inspired by a meeting with Islais Creek, a forgotten river of San Francisco. Beside the creek, I saw a map that showed the major historical and strangely absent rivers of San Francisco. Seeing that map was a powerful experience. Almost like I’d been given a gift and had it taken away in the same moment. But as I continued to wonder where these bodies of water went, I realized that the gift of those rivers had not been taken away completely. They were just under my feet. Somewhere buried. And that changed my whole experience of walking around San Francisco.

Now, I pay attention to water when I see it and watch where it’s going. I seek out the sound of our ancient rivers gurgling under the Department of Public Works sewer manholes (they are there!). I imagine digging through layers of cement, through old abandoned ships and other miner rubble that filled in the bay, to arrive at the mouth of the ancient rivers that continue to carry San Francisco’s minerals and freshwater into the salty bay and Pacific.

The next water map that changed the way I see things is a map of California’s waterscape before Europeans came. It, too, has features I don’t recognize. For instance, a giant lake at the end of the Central Valley, called Tulare Lake, that is bigger than Lake Tahoe. Only a dry lake bed, erased from most modern maps, survives. Also missing, are giant stretches of freshwater marsh that stretch all the way from North of the Bay Area through the Sacramento Delta, covering the Central Valley to its southern end. The San Joaquin River regularly left its banks and flooded the Central Valley during the spring and winter, creating a vast and fertile freshwater marsh. Saltwater marshes are also absent from the mouths of rivers in Northern and Southern California. Marshes that supported Tule Elk, beaver, and Grizzly Bears, a bear that was so common and abundant it became our state animal.

Modern maps of California’s waterscape are very different from the pre-European one. Looking at a map today you would see two of our major rivers, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin, as solid blue lines, but in reality, the map should show dotted lines; to show all the stretches that have been dewatered, being diverted to other uses such as drinking water in Southern California and farming in the Central Valley.

would see two of our major rivers, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin, as solid blue lines, but in reality, the map should show dotted lines; to show all the stretches that have been dewatered, being diverted to other uses such as drinking water in Southern California and farming in the Central Valley.

Today, in a state with an incredible amount of rivers and watersheds, 20,000 miles of rivers forming 60 major watersheds, only one watershed, the Smith River’s, is free of dams. And modern maps include strange new bodies of water, reservoirs and lakes, some of which used to be valleys that were flooded for water storage. The Salton Sea is great example of a ‘new’ body of water. The historical map shows the Salton Sink, an extremely salty, low-lying area that flooded from time to time, but was generally dry. Now, salty Colorado River water and farm run-off collect to create the Salton Sea, luckily, at the same time creating a habitat for water birds that were displaced by development on the Southern California coast.

Seeing the original waterscape of California is a blessing and a curse. It is incredible to understand how California looked and where water naturally wants to travel. To know about ancient bodies of water I didn’t know existed. At the same time, it’s hard to be given a precious gift and have it taken away. It is heartbreaking that I never got to see California at its most wild and abundant and flowing.

But on the other side of grief, there is acceptance and possibility. Ok, so our landscape, water and otherwise, has been irrevocably changed. For a moment, let’s change our perspective and acknowledge how incredible it is that humans can alter their environment in such significant ways. In the 1940s and 50s, when most of California’s major water infrastructure was being built, there was a feeling that human know-how and engineering could overcome any obstacle that nature threw its way. The only problem is, we succeeded in overcoming nature. And nature is the source of our water, our food, our air, our lives.

And so here we are. In a time where we realize, we must work with nature, not overcome it. Here lies possibility. We cannot go back to the map of California’s waterscape past. But we can use it to understand where water naturally wants to flow, and how to support water in bringing us its abundance. Instead of forcing water against its will to go where we want it, we can observe and guide it to where it will naturally do the most work for ecosystems and by extension, for us. We can coax it back into wetlands, the nurseries of wildlife and the most biologically productive places on earth. Just as we can coax it to saturate our farmland with fertility. Just as we can harvest and recycle water directly where it falls in our urban areas.

If in one century we could alter the landscape in such a profound way, we can do it again. Only this time, we’ll humbly remember who the hand is that feeds us.

Sources:

Introduction to Water in California, by David Carle

KQED documentary, Saving the Bay

Header Image: by Gary Stolz, public domain photo from the US Fish and Wildlife Service archive.

River Image: present day San Joaquin River, public domain from the California Central Valley Water Board