The story of the Imperial Valley is not only the story of humans making a desert fertile, but also woven into my story. My great-grandparents met and fell in love there, in the tiny town of Brawley. And their story follows the development of this desert in the most south, most east part of California.

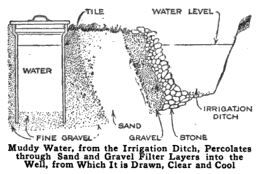

That was what it used to be called, the Colorado Desert. And that was what it was- ‘just’ a desert- the desert west of the great Colorado River. A few smart men saw the very dry, yet very fertile soil east of the river and decided to ‘civilize’ the place. In 1901, a large canal was opened from the Colorado into desert. From the desert, lettuces and grapefruit, melons and tomatoes came. An Imperial Press newspaper from 1901 proclaimed under its heading, “Water is King- here is its Kingdom!” A kingdom built on desert.

By 1902, Southern Pacific railroad laid tracks into the desert, now renamed, the Imperial Valley, by a very smart business man who knew the value of an enticing name. The town of Brawley was added to the map around then.

business man who knew the value of an enticing name. The town of Brawley was added to the map around then.

Vegetables and fruit piled up in bountiful baskets. And with so much abundance and a wealthy of opportunity, people came from all over. After all, not only were they growing food from what looked like wasteland, because of the climate, they were growing food ALL year long. Everyone wanted to be part of this great experiment, that sparked the imagination of every American mind.

Which is when she came onto the scene. In 1916, my pretty little great-grandmother, Delia Campbell, arrived in Brawley at the sweet age of sixteen. She came straight off the farm in Oklahoma- used to working hard, riding horses, and cooking up fried chicken and corn bread. Her father had gotten a job, unrelated to farming. And so the family came and settled.

Two years later my great-grandma met a young chap named Sam and became Delia Dotson when she was just 18 years old. The family moved away from the Valley for some time, to San Diego, to El Paso, Texas with the story of the Imperial Valley picking back up with my grandmother, Millie Delong.

Her family moved back to Brawley when she was ten years old in 1936. Growing up, I always remember my grandma mentioning how much she loved Brawley.

“It was a beautiful town. Everyone knew everyone,” she recalled recently.

She told the story of a small town- of just 10,000- a wealthy agricultural town. A town overflowing with giant heads of winter-grown lettuce. In fact, a point of pride, was that the Imperial Valley always sent the first cantaloupe, watermelon, and lettuce of the year to the White House. The desert climate made it possible to grow all year long. But without water, the Kingdom would have come crumbling down.

My grandma remembers how a certain produce driver on the way to the market would stop at her house and give my great-grandmother loads of giant melons and heads of lettuce. She remembers the kitchen counter always full of produce.

She remembers going to the opening of the All American Canal- the lifeline of the Imperial Valley and the largest irrigation canal in the world- how the US Secretary of the Interior was there.

And she always recalls the story of the 1940 7.1 earthquake that nearly shook Brawley apart. That was when her family moved- picked up again and went to San Diego where the rest of history played out and led to a little baby named Me.

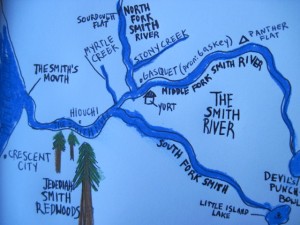

The Colorado River

I had to pay a visit. Being so close and all. When my mom and I finally found a small stretch of the Colorado, in an RV park, we found a modest river- not the raging Colorado you see crashing its way through the Grand Canyon. No, this river is an all but spent river. Most of what it carries is run-off from farm irrigation. Soon, it crosses the Mexican border, and before it gets to its old delta in the Gulf of Mexico, is pretty much used up.

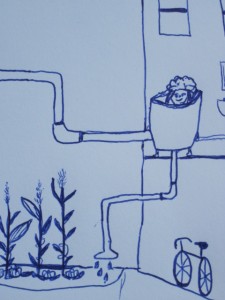

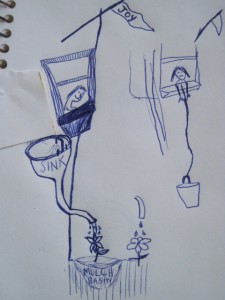

I felt bad, but I didn’t really want to touch the water, muddy with fertilizer and farm soil. This river that helped sustain me as a child. As a San Diegan, about half the water I drank was from this river. This river, classified as a deficit river, because more people own water rights to it than there is water. I had to stop and pay homage- to this wild creature, wild and now tamed. But giving us ‘civilization.’ Producing over $1 billion in agriculture a year, and providing homes for many people.

So many times in southern California, you can look around you and see that the mirage around you is made of water. The gift of a loving mother, a particular river, created our economies of agriculture, industry, Hollywood, SoCal suburbia….all of it.

The Colorado continues to give. And give. And give.